Hello Pascal and friends! 🙂

There’s been some renewed discussion about faith and evidence in the last few posts and comments. I’ve touched on my issues with “faith” in previous posts like Is Love a Good Reason to Believe?, including why the word makes me uneasy as a non-believer. It’s been a while, though, and this is an important topic and we should try to come to an agreement while we’re covering it.

Pascal, in the last post you quoted Mike who had said the following:

… I’m certainly not adverse to … doing my best to convince others to embrace evidence based thinking instead of faith.

Thank you for the guest post, Mike! Very well done! 🙂

After this quote, Pascal, you highlighted that faith and evidence may be an acceptable approach for you and not an acceptable approach for me. You said:

… Russell and I have often reached a point of impasse here. Is the word instead correct? I feel that it is the pivot of the sentence at least, likely the paragraph, perhaps the thesis.

Let’s reason this out and clarify our differences. They may not be as stark and opposed as it seems. I have the floor while you’re hiking a mountain with your amazing family, so I’ll explain what faith means to me and you can tell me where you find disagreement.

At the risk of being far too long winded and spending too much of my limited time on this post (it’s already after 11 PM and I have an early start to a busy week tomorrow), I’ll try to keep this much shorter that I want to and save details for follow-up comments. Who am I kidding. That just means it will be 4k instead of 10k words. Haha. Onward.

Whether or not Socrates actually said this, I find it both cliché and extremely relevant.

The beginning of wisdom is the definition of terms.

What do we mean by faith? If communication is a transference of an idea from one person’s mind to another person’s, and if information theory (I’m almost finished with The Information and it’s one of my favorite books) cares about how accurately that idea is replicated, it seems essential that we cancel out the confusion and noise caused by potential meanings we don’t intend when we use words like “faith.”

Here are a few of the many, many potential things that will come to someone’s mind when one mentions faith. This is all off the top of my head, and I’m sure each of you can add many more. The point I want to make is that they tend to fall into three basic categories. Some definitions put faith in a positive light, some a more neutral, and some are more negative.

Neutral definitions of “faith”

1. Hope

2. Desire or expectation

3. Belief, confidence or trust in a person, object, religion, idea or view. (Dictionary.com)

Anti-faith definitions non-believers tend to hold

4. Blind trust, in the absence of evidence, even in the teeth of evidence (Richard Dawkins)

5. Believing something for no good reason (Matt Dillahunty)

6. Only needed when there is insufficient evidence to hold a desired belief

7. Wishful thinking – I hope it’s true therefore I have complete confidence

8. A bias, especially special pleading, that is thus less likely to lead to truth

9. That which is required to move one in a desired direction from a position of non-belief to a position of belief

Religiously-based definitions of “faith” that believers tend to hold

10. The substance of things hoped for and the evidence of things not seen. (Heb 11:1)

11. Complete trust or confidence; based on spiritual apprehension rather than truth (Google or Siri grabbed this from somewhere)

12. An educated decision about a personal religious conviction, based on evidence, and not blind

13. A virtuous quality (something worthy to be desired, the more faith you have the more righteous you are) that makes one right with God

14. That which is granted by God to some, in varying degrees, in order to fulfill his plans.

See the Christianity section of the Wikipedia page on Faith for more interpretations.

What follows is my take on these definitions and some recommendations to readers that might help more of us increase our understanding of one-another’s perspective. Let me pause here and say that my view is not “the right view.” People come to this from different angles and my goal is not to convince anyone that X is how faith “should be interpreted.” What I hope to do here is clarify “why,” in many cases, there is disagreement between believers and non-believers about the virtue of faith. This comes from my own limited perspective, so add it to yours only if it helps. 🙂

Why the neutral definitions of faith (1-3) should be avoided

Recommendation #1: Don’t use “faith” as a substitute for a better word with a clearer meaning

If we mean something like #1-3, we should consider using words other than “faith” unless we are certain that everyone in the audience is on the same page. When we replace perfectly good and appropriate words like, confidence, trust, belief, etc., with nebulous words like faith, we risk causing some to misunderstand our meaning due to the ambiguity of “faith.” For example, if you believe in Young Earth Creationism and you tell an atheist she “has faith in Evolution or Darwinism that is no different from the faith you have,” you’re conflating two different definitions in the mind of your audience. I’ll explain why in a moment. If you use the word “confidence” instead of faith, you remove this ambiguity. You also reduce the chance that a non-believer will assume you mean “religious faith.” There is a strong difference between confidence, or trust, (terms where “faith” is often inserted) and religious faith. It’s this key difference that is usually being conflated in most of these scenarios. So, if you mean confidence, say confidence. If you mean trust, say trust. Save “faith” for religious faith, unless you really know your audience and “faith” fits what they’ve expect for the context, or unless you’re willing to take the time explaining what you mean in more detail.

Why non-believers should be cautious when using the anti-faith definitions (4-9)

If we choose to assert, like Dawkins did (#4), that the trust girding faith is blind, we are erecting a straw man. Perhaps you can think of a belief that isn’t based on some evidence, but I cannot. The question is not whether evidence is present, but whether that evidence is of the caliber that warrants the level of belief a person is assigning to it. Dawkins does have a point that some faith, particularly some religious faith, is held in spite of what should be compelling evidence in opposition. However, the pivot is here: compelling to whom? They have sufficient evidence in their mind, or, by definition, they wouldn’t believe what they have faith in. Is their manner of reasoning about their evidence grounded in a mechanism that is more likely to lead to objective truth? That is the key question.

Definition 5 also turns on this point. What is “good” evidence? That is where the believer and the non-believer tend to differ, and it is the real heart of the issue about the meaning of faith. I just made up definitions 6-9 but most of them probably came form my subconscious after being reconstructed from something I previously heard. As a non-believer, I should be careful before thinking of faith this way because each use of the word requires it’s own evaluation. People often don’t mean “religious faith” when they say “faith,” and even religious faith doesn’t always meet the criteria listed in 6-9.

Why non-believers tend to distrust the religious definitions of “faith” (10-14)

First, let me say that I have immense respect for faith. I know that statement won’t sit well with many of my fellow non-believers, but I must be honest. I know the indwelling presence of joy and strength that comes from faith first-hand. It is a confidence, an assurance, an acceptance and a love like no other. Neuroscience might note that it can act like an addiction and a high like any other positive endorphin trip. That doesn’t change the experience. I just wanted to start by identifying with the believers before I explain why the feelings, while deeply treasured, are still subject to the assessment that follows.

The first definition in that set (10) makes faith sound like something to be avoided – at least that’s what the rational parts of my conscious mind say (some believer’s may call that the devil). Paul sounds poetic and it’s in the Bible so a vast number of people take it to be God’s definition and wholly accurate. This is just the KJV but please look up the possible meanings of the words in the Strong’s concordance. I use this almost every time I look up a verse in the Bible. Here’s the link to Hebrews 11:1 where this faith verse is recorded. Click the words to where else they’re used in the Bible. Click the Strong’s numbers to see the possible meanings that the words may have.

The problem I’m seeing with Paul’s definition is the same problem many non-theists probably see with most religiously based definitions they hear. Non-theists, this is my personal assessment so please let me know whether or not you agree with the following. Religious definitions of faith are in opposition to the best tools of reasoning we have for determining Truth.

I experience the sublime, but at the end of the day, the substance of hope is really best described as just “hope.” “Evidence of things unseen” is either no evidence or weak evidence, in my opinion. So, in a sense, it seems as though he’s defining faith to be hope, courage, conviction, etc., that is based on non-testable and weak evidence. That sounds very much like poor reasoning that doesn’t take advantage of what we’ve learned about coming to true beliefs since Aristotle (before Paul) and in the scientific revolution in the last four hundred years. It was written before modern philosophy of science so we can’t expect it to have taken that into account, right? The two problems that keep that from being convincing to me are that it was written post-Aristotle, and it was supposedly divine. It could have used Plato/Socrates/Aristotle-like reasoning as a basis for determining which beliefs to hold with which level of certainty, but it did the opposite and left the door open for almost all the fallacies and biases of human reasoning to enter what we accept as true. Despite 1 Thessalonians 5:21 which tells us to test all things, we aren’t given any tools for testing that will have a high chance of leading us to truth. Testing them against the Bible is circular and thus shouldn’t be believed with full-confidence. In addition, Biblical faith makes predictions that are testable and don’t pass the test when measured (e.g. the average success-rate of prayer).

Please don’t write me off as a post-modernist strong-naturalist steeped in scientism. I’m actually none of those things, by my interpretation of them. I have reasons for believing what I do about epistemology and the good brought about by the modern philosophy of science. I don’t believe it’s the answer to every question, but I know what it’s strengths and limits are. Coming to “true beliefs” is a strength it has over “reasoning without it.” More on that in a minute.

Definition 11 isn’t any better. If complete trust is to be based on spiritual apprehension rather than on truth, this highlights the problem neatly. It’s about what we value more – a false belief that feels excellent out of the box or a true belief that we have to work at before it will feel good after leaving the false belief.

Please note that I’m not saying anything about the truth or falsity of the beliefs the Bible relates. All these arguments are equally applicable to any religious, political or other ideology. The question is not whether the Bible’s claims are true or false, but whether or not the mechanism it outlines for belief is one that is more likely to lead to True beliefs. As Matt Dillahunty has pointed out, our goal should be to minimize the number of false beliefs and maximize the number of true beliefs we hold. We should all strive to hold as many true beliefs and as few false beliefs as possible. If that’s our goal, we must recognize the following.

Promoting certainty of belief in concepts that we hope are true, but for which we have little evidence, is a poor method of coming to objectively true beliefs. It may make us feel good, but even if it leads to a belief that is true but non-demonstrable, we can’t relate that knowledge to others because it’s subjective by nature. In that case it is indistinguishable from the follies of our bias reasonings and logical fallacies which, when discovered, leave many of us either deeply questioning our faith or deeply opposed to what we see as the “religion of science” or “liberal intellectualism.” Any angle I examine it, I can’t find Paul’s definition of faith to be more virtuous, righteous, or valuable in terms of leading to truth than evidence-based reasoning. If truth is individual, given by God, and steeped in a web of flawed human reasoning that opposes the order or critical thought, then I still want to know it but I can’t get there.

Definitions 12 through 14 don’t make religious faith sound any more desirable, to me personally, as a path to truth. I made them up anyway. Saying a decision is educated also makes it more prone to the the MR thing I wrote about in Why I respect Pascal (I won’t write the words here since I told some important people that I’d stop mentioning it :)). Definition 14 is actually the one I’m the most okay with because it has a clear meaning within the religious context and doesn’t prescribe anything directly about how we ought to reason. I find it dubious, but I don’t take umbrage with it. I used to believe I had it and I miss it.

Why else do non-believers feel uneasy when someone says they have faith (and don’t clarify that they don’t mean religious faith)

I want to wrap this up quickly but there is a lot to cover here. I’ll try to make it quick and save most of what I was going to say for a later time. The short answer, in my opinion, is that religious faith tends to demand a level of certainty beyond the level for which it can justify good evidence.

A wise man proportions his belief to the evidence. – David Hume

When I say good evidence, I do mean evidence that can be tested and falsified. In Paul’s time, personal conviction may have been “good evidence.” I don’t think so, because he had Aristotle who’s principles would have led to much better evidence, but then again, Plato’s logic include “forms” and was more of an armchair philosophy compared to the modern empirical sciences which are significantly more accurate. Either way, it seems undeniable to me that, by today’s standards, Paul’s definitions of religious faith do not qualify as good evidence today. Why?

First, listen to this audio lecture. Seriously. If you do I’ll celebrate your awesomeness in a post and email you a secret family dessert recipe. Pascal listened to it. 🙂 I know you’ll like the course because you read this far. If you made it this far you definitely have what it takes to make it through that awesome audio.

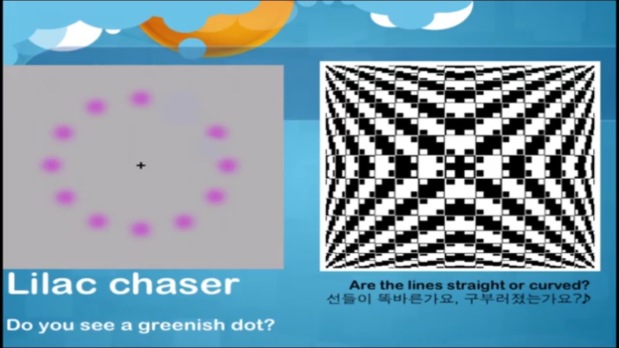

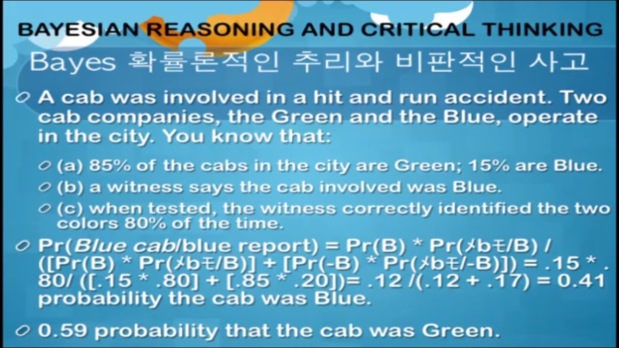

Second, briefly, science is a subset of reason. Life forms have been reasoning about the world, their environment, themselves, each other, etc., for millions of years or more. Humans for hundreds of thousands. That reasoning power is great at self-preservation, but not engineered for finding truth. There are many flaws in our reasoning. For an idea, read The Problem, and skim the Wikipedia pages for cognitive biases and logical fallacies. The vast majority of these effect each of us every day and we are completely unaware. This is another excellent audio book on the subject. The bottom line is that if there is an objective reality (and I believe there is), we do not observe it. We construct our reality as we experience it. I’m not even talking about quantum physics here. There are several layers of processing that occur between what IS, and what we consciously experience. Those layers are faulty at many places and lead us away from the truth of what IS. Worst of all, we aren’t even aware of it most of the time. For a taste to demonstrate the principle, look at the famous dress photo (blue and black or white and gold?) and these others I got from a TED talk a while back. There are many more such images. You can find similar images by googling “optical illusions” but Neil Degrasse Tyson says we should call them “brain failures” because that’s what they are…

Okay, so our human reasoning isn’t perfect at seeing things, but we can still trust our non-scientific reasoning about things, including the supernatural, right?

Not so much. 🙂

The philosophy of science has evolved over centuries as the most effective means of stopping poor reasoning that plagues all humans. A good scientific theory provides explanation, prediction and control. We can justify belief in many concepts, but confidence should be reserved (in my opinion) to a more moderate level when dealing with things that fall outside of what we can test. The appropriate level of confidence almost always falls below the threshold of what would be considered righteousness in a religious tradition. Religious faith demands a level of confidence that is at war with the best processes we have for searching out truth today. I am not saying that science is the only way to “know” something. I am saying that we must acknowledge that our non-scientific reasoning should be distrusted to a greater degree than our reasoning that follows the scientific process accurately. Science embraces methodological naturalism which means it doesn’t say anything about the supernatural one way or the other. While it won’t tell us what God’s nature is, it can attempt things like determining which clearly defined hypotheses are less likely than others based on the predictions those hypotheses make (assuming they interact with the world in some way).

We can believe X about God Y, but if we have the same level of confidence about how many angels can dance on the head of a pin than we do about whether the sun will rise tomorrow, we’re placing as much confidence in our demonstrably far-less trustworthy evolutionary reasoning as we are in our reasoning based on science, which is encompasses the latest advances in thought throughout history (with a demonstrable track record of high-success).

The real issue is whether or not something is falsifiable. If it isn’t, we can still believe it and potentially justly so. But we can’t call it science. Popper helped solidify that with his problem of demarcation. Science which encompasses mathematics, statistics, probabilities, confidence intervals, margins of error, peer reviews, efforts to disprove hypotheses, checks against personal biases, double-blind trials, and the formidable advantage of formulas and logic to weed out the ambiguous nature of human reasoning and language – is far more likely, on average, to lead to true beliefs (beliefs that accurately reflect the reality that is) than using non-scientific processes based on flawed reasoning and circular logic about how we feel about a given subject.

If you disagree, I’ll be happy to dedicate a post to defending that position. Before doing so, consider that most religions require an ante of belief upon conversion. You must believe X and Y to be a true follower of religion Z. Once there, the balance between eternal bliss and eternal torment due to apostasy often hinges on your level of religious faith. With that in mind, consider Bill Nye’s answer at the end of the Creation vs Evolution debate about what would change his mind. A single piece of evidence (paraphrase). His opponents answer was “nothing.”

Please don’t think I’m saying that all believers hold faith “in the teeth of evidence” or that Ken was not right to do so. Perhaps he does have the proper belief or perhaps he would change his mind when the right pieces of evidence appear, but he just can’t imagine it yet. What matters is not whether faith in X or Y is warranted, or even whether idea Z is true or false. I’m asking you to consider which process of reasoning, on average, is more likely to yield more true beliefs and fewer false beliefs. Regardless of your answer, know that non-believers tend to think that the methodology of reasoning is different for religious faith than it is for science (yes, they conflict), and that religious faith is far less reliable. That is why they tend to define it differently and why it makes them uneasy to hear someone say they are using “faith.”

Conclusion

The word “faith” means so many things, many of them very polarizing, and there is almost a certainty that people with opposing theological beliefs are not going to accept the same interpretations. We all have flaws in our reasoning, naturally, from birth – especially me. No matter how much we try to overcome them through learning about them or studying logic, biases, meta-cognition, etc., none of us are completely immune to the hidden biases that creep in. For this reason alone, we should be cautious of the types of reasoning that make us certain about untestable claims. We should also be aware of when we think we’re testing claims against our experience but we’re really failing to take account of confirmation bias, or other biases for which we are often unaware until we learn about them and examine our beliefs against them.

Is faith good or bad? I may be largely a personality thing. Evidence seems to support the idea that some personality types (mainly “feelers”) tend to be more likely to land on the pro-religious-faith side than their opposites. I don’t know if that’s true, but the Myers-Briggs profile analyses seem to say so.

In some sense it depends on how important truth is to you. Faith feels wonderful. Oh how I miss it. But is the quality of evidence in religious faith sufficient to warrant the level of belief we hold in our religious tenets? Those who reason by faith usually say yes. Those who don’t tend to say no. Who’s right? As a general principle, my assessment is that religious faith is less trustworthy than scientific reasoning, so I trust it less. I do not completely distrust it but I’m a little more skeptical of it. I think this is good because wanting something to be true means we should be even more cautious of it, examining it even more, because our natural tendency is to do the opposite (another blind spot).

So Pascal, if we’re talking about how we reason as humans, I think we should focus on evidence-based reasoning over faith-based reasoning. I actually think that’s not the best way to consider the conflict. I still want there to be faith-based reasoning because the things that come to us through our faith are a kind of evidence. It’s all under the umbrella of human reasoning. We just need to subject our faith-based thoughts and intuitions through the same two filters that we subject every other kind of thought.

Filter 1: a list of all the biases and logical fallacies we’re subject too.

Filter 2: evidence-based testing (e.g. scientific method, testing, repeatability etc.).

We shouldn’t necessarily disbelieve it if it fails one of these filters, but the degree to which it passes both filters is the degree to which we should trust it, wherever it comes from (faith-based reasoning or elsewhere). This is where I support the “and” over the “instead.”

To me, “faith” is a red-flag warning of potential belief that exceeds what’s warranted by the evidence. I see faith as a potential multiplier that takes what we should believe based on evidence and boosts it some degree with confidence from what we want to be true. Evidence always informs faith, but faith has a tendency to go further than good, fallacy-filtered evidence warrants. If we hold up the white-flag of humility alongside the red-flag of hope (e.g. if we say, “I think and hope this but I don’t know”), then I’m much more okay with faith and evidence rather than limiting to just faith instead of evidence. Of course, you have this quality in spades. Go climb your mountain, you awesome dad. 🙂

Next week, let me know if we’re at an impasse with faith and where I made things more confusing or more clear. I know you already knew the vast majority of this, but I’m putting it down for posterity and the off chance it might help someone. Sorry you had to wade through it. Please forgive the typos. It is very late now.

Questions

Readers, did any of you make it this far? If you’re a non-believer are you uneasy when people say you “have faith in X?” If you’re a believer are did this post irritate you? Do you disagree? If so, I apologize. Want to add anything?

Gentleness and respect,

–Russell

Hi Russell, I made it through, I’m a christian and I think (1) you had a lot of good thoughts but (2) I think I see things very differently (I suppose obviously). Here are just a few thoughts to throw into the mix:

It is possible that faith to believe what is true is given by God (the Bible suggests that, as does your #14). If that was true, it would explain a lot – why some believers are so confident and most non-believers are so critical – and hypotheses that explain a lot are worthy of some respect. You could say that it wouldn’t be a good basis for belief, it is bad epistemology, etc, but it might still be a true belief. Of course, this would be a conversation killer, because an unbeliever couldn’t accept it, so I won’t mention the thought again. But I guess it needs to be said.

We would all probably agree that our epistemology should be appropriate to the subject (e.g. we don’t use the scientific method to test if we like chocolate or if I love my wife), the circumstances (e.g. in an emergency, we take shortcuts or we may die) and who we are (e.g. don’t ask a five year old to solve Fermat’s Last Theorem). The following is a list of things which require, in my opinion, different levels of evidence:

whether to try the new flavour chocolate or stick to the old favourite

whether to ask this woman to marry me

whether to choose this job or that one

whether war is justified

does the multiverse exist?

whether this new drug should be released onto the market

So is something like scientific method appropriate to knowing God? Or is some thing more like how we decide to get married or accept a new job? (Non-believers often say “but choosing to get married is different because you know the person exists”. But I am not suggesting the two matters are totally analogous, only that both involve quite life-affecting decisions made without certainty of the end result.) And the key in these cases is surely choosing what has the preponderance of evidence and the least amount of uncertainty – a standard that wouldn’t be sufficient for science and probably not acceptable in a court of law – plus a certain amount of faith or trust in the character of that woman, despite the uncertainty.

My opinion as a christian is that the preponderance of evidence is in favour of God and Jesus. I think that there is evidence either way, but I think the pro evidence significantly outweighs the anti. I accept that you make a different judgment and this topic isn’t the place to discuss our different assessments. But I think it is reasonable to make the decision to trust Jesus was telling the truth, and to trust him in a way not all that different to how I trusted my wife when I asked her to marry me.

So, finally, where is “faith” in that? Which definition am I offering? I am happy with #3 (and I would be happy to use synonyms instead), I think Hebrews (#10) is a quite reasonable definition, because it simply points out that many intangibles can never really be “proven” like tangibles can. Another way of expressing my view would be: faith = living confidently (though not with certainty) following a belief that is merely probable and not certain, because I have decided the evidence points to the truth of trusting Jesus. Again, it is similar to being married. I may not be certain this woman is the very best for me in the whole world, I may not be certain that someone “better” won’t come along tomorrow, but having decided this is my best choice, I will live on that basis regardless. Does that make sense?

Thanks for your thoughtful ideas, I hope I have helped the discussion along.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hi UnkleE. Thank you for the thoughtful comment. I actually largely agree with this. I’ll explain my differences and where I have problems with it when I get a work break. 🙂

Gentleness and respect,

—Russell

LikeLike

Hi unkleE!

I apologize for what is about to follow. Some people don’t like the style of quoting and responding to every line. My goal is to get as many of my thoughts out as possible in a short time and to not miss addressing any of your points. I hope this doesn’t offend you. Here goes. 🙂

I agree with your point and tried to pull out my version of it a few times in the post but I probably didn’t do a good job. Many non-believers (and seemingly even many non-humans) believe True things so if it is God granting that ability, he must be doing it to some degree for everyone.

Explanation is only one leg of a good hypothesis. There are an infinite number of hypotheses that can explain the data. Explanation of some of the data does not warrant confidence in a hypothesis. If the explanation accounts for all the data, is clearly defined, is coupled with accurate prediction (and sometimes control), is filtered through the fallacies of human reasoning, and is the best explanation we have given (or at least as good as alternative explanations) at explaining the data, and if it requires the fewest assumptions in addition to what we can demonstrate – only then is it worthy of belief (with a confidence level and a margin of error). Otherwise, we can respect the hypothesis, but trying to justify confidence in it would put as at odds with the best level of reasoning about truth, and many of those who don’t find the hypothesis compelling will just be labeled as those that God didn’t choose (or chose and then release from truth when they learned to much about the more sound processes of reasoning today).

If you are interested to think through the argument your proposing in your first quote above and present it as an actual hypothesis, I’ll do my best to explain why I think it fails and why I think there are better hypotheses that are simpler, with fewer new dependencies, that also fit the data, make accurate predictions and provide control.

I’m glad you said it. I said it in the post and I agree. I don’t think it’s bad epistemology for those who haven’t been exposed to the alternatives which are better. It’s the natural epistemology, but unfortunately it’s flawed and leads to religious feuds. I’ll also add (I mentioned this in the post but it might not have come out as clearly as I wanted it to), that bad epistemology is certainly not limited to religious faith, not all religious faith is based on bad epistemology (some is just good evidence that has no need for “faith” but is labeled as “faith” because that is seen as a virtue), and that many non-religious ideologies can fall into the camp of religious faith regardless of whether or not they are religions. It’s not even about religion other than the common theme of religion requiring an ante of high-confidence that is perpetuated through the life of the believer while condemning the changing of one’s mind about key tenets. Any system of non-evidential reasoning has similar problems. They let the preponderance of human fallacies run wild and, as you stated, are often not based in good epistemology. Also, these are obviously all generalizations. It is certainly possible to hold religious beliefs about God that are based on good epistemology because they have been passed critically through the two filters I listed. The first filter basically gives alternative reasons that could explain our beliefs (which we should consider). The second filter says which of our beliefs we should probably doubt for evidential reasons that conflict with reality as we observe it. I think many readers of this blog, including Pascal and probably you, have subjected many or most of their beliefs through these filters and have an appropriate level of confidence assigned to them. The post was about the concerns of faith in general and not with individuals’ use of faith.

I wouldn’t claim that we should be actively using the scientific method, specifically, for all areas of life. What I do believe is that we should examine all our closely and confidently held beliefs and pass them through the filters I mentioned. There may be some we need to shore up. Why do we believe X or Y so strongly? What is our evidence and is our confidence level appropriate for the evidence we find, or have any of the fallacies from the first filter affected our confidence level to an inappropriate degree? Whether we like chocolate, a quick decision about a route, or expecting unreasonable math from a child aren’t relevant to this in my view. With that said, science actually can provide a good approach to reasoning about all of those, but that’s outside of my point.

Completely agree. 🙂

The answer is a resounding “no.” Science excludes the possibility of knowing God by setting one of it’s key principles to be matching natural phenomena to natural explanations. We knew there was a problem with burning people alive for being witches. Reasoning without a formal methodology that ignored supernatural theories led to all manner of crazy subjective reasoning (largely based on fear of what strong person or group X feared about their deities or thought their deities wanted from them). It was an unstable system. From 2:46 to 4:21 of this video is tangentially related.

No, science does not help us know what God is. Science tells us what God is unlikely to be. The way it does this is by providing a formal method to determine whether claims should be believed or not, and with what level of confidence and what margin of error. This is the point of the second filter I mentioned. If a claim about God does not involve properties that interact with he world in any testable way, science is completely mute on the point beyond a sprinkling of Occam’s Razor. If the properties of a deity do make claims that interact with the world, then those claims are subject to testing by science, and one’s confidence in one’s beliefs in the truth and existence of a deity with such properties should take those scientific results into account.

Having said all that, I think the very idea of “knowing God” through any means is wrong-headed. God is by definition supernatural. Outside of nature. Because of that, our thoughts about God are indistinguishable from our imaginations about a made-up God, except where our ideas of him require interaction with the physical world – in which case, science is the only way we can “know” anything about God (which is strictly limited what properties he probably does not have).

Those are decisions that we have to reason about and the best way is to pass them, as much as possible, through both filters I mentioned.

The processes in a court of law are mostly science-based. Science acknowledges subjectivity and works with the evidence it has, even the terrible reliability of eye-witness testimony that hasn’t passed through the two filters or the feelings of someone in love. I wouldn’t call what you describe “faith” in the woman’s character. The confidence level should be entirely based upon the evidence after being passed through both filters I mentioned. To come up with a level of confidence or trust, etc., there’s no need for anything beyond the evidence itself. Unless we can separate where confidence from the evidence ends and a desired level of trust that goes beyond that begins, faith isn’t needed here. Hope that the supporting evidence will continue past the marriage ceremony, perhaps? Hope, I’ll go with that. 🙂

I understand and respect this position. I used to hold it myself. I’ll just say that I can’t find any way back to that place, despite how much I long for it, because no set of reasons for trusting the Bible that I can come up with are not better explained by the reasons to distrust it. I was taught to love it before I knew what critical thinking was. It took years for me to learn meta-cognition and then have the courage to critically examine my beliefs to see where I could actually stand without feeling dishonest.

This is where Pascal stands, and where many do. The theme is something like, “I trust Him like I trust my wife’s love.” And then, ultimately, “I trust because I’m in love.” This is where the disconnect usually occurs. My response to Pascal can be found in Is Love a Good Reason to Believe?. Yes, as you pointed out, I trust my wife’s love because she’s here in the flesh telling me in small ways every day. I used to trust Jesus’ words because I believed the Bible was worthy of trust and Jesus was here, telling in small ways every day. If you still believe that and if you’ve examined your belief through the filters I mentioned, your belief is well-grounded. However, if I could give you 5 seconds in my mind you would understand why I don’t trust it, and it all comes down to those filters. In my view, the Bible is clearly less than fully trustworthy and it’s difficult to see which parts are worthy of high confidence. The presence of Jesus or The Holy Spirit in my life were better explained by my misunderstanding and misuse of that first filter I mentioned.

I think synonyms for 3 would be better when you’re audience includes non-believers to reduce the chance of their gut-reaction being “My beliefs aren’t outside of what the evidence warrants.”

I also think Hebrews 10 is a reasonable definition, and the fact that intangibles can’t be proven (demonstrated to be True) elucidates the point that they should rarely be trusted to the same degree as the tangibles that are proven. Logic work with proofs, but science and logic are not completely overlapping circles (depending on your definition of science as the inclusive or exclusive version – I see science as encompassing logic but that’s more the inclusive version). Science, outside of formal logic in the domain of mathematics, doesn’t seek to prove anything but rather disproves hypotheses by demonstrating which ones don’t fit the data. To use “proven” as a word to cast doubt on the scientific methodology is targeting something that is outside of the scope of science compared to what the user of the word “proof” usually intends. I don’t think you were doing this with your use of “proven,” but I wanted to point it out in case it helps others (not that anyone else will read all this… haha).

It absolutely does! 🙂 I would just ask this. If you took out the faith part, and just trusted Jesus based on the evidence alone, and trusted your wife was right for you based on the evidence alone, would it change anything? If not, then what is faith doing in your belief equation? Why use the word at all? If it would change something by putting it back in, then isn’t it giving you a level of confidence that exceeds that which the evidence warrants? If so, do you feel comfortable knowing that your confidence level is based to some degree on your desired truth rather than evidential truth? Doesn’t this validate the definitions of faith that indicated desire acting as a modifier to confidence, as I wrote about in the post’s conclusion?

If we 1) seek to understand as many of the flaws in our reasoning as possible (that book I linked is an excellent start) and 2) examine all our closely held beliefs (including those about God, our spouse and loved ones, our political party, etc.) and subject them to the two belief filters I mentioned, whatever beliefs and confidence levels come out on the other side are likely to be much more objectively valid and worthy of respect from others. If we fail to understand our flaws in logic and our biases through a lack of awareness of meta-cognition, our reasons for holding our beliefs are no more trustworthy than those of the children fighters in ISIS.

Faith has great value, but we start life under it’s control. It’s not perfect. Some learn it’s weakness and shore them up. Others are swept along for the ride and go along with whatever their in-group thinks. This is why most religion is based on location and why there are so many religions and sub-denominations today. It’s also why I question faith as the best method to obtaining more true beliefs and fewer false ones, in general.

Oh goodness. I just overwhelmed you with words again. I’m so sorry. I completely forgot that my wife limited me to 1800 word posts and 5 sentence responses. Ah. I’ll try that next time. It’s back to work for now. I hope this has helped in some way and I hope you have a great day! 🙂

Gentleness and respect,

–Russell

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi UnkleE if it is the case that faith is given by God then what does that mean in regard to the person without faith. Does it mean that a sovereign God, creator of the universe has decided before they were even born that they will not have faith. What are they to do then?

LikeLike

Hi Peter,

I’m sure you’re aware that some christians think what you say (that God predetermines who will believe) but I don’t believe that.

(1) The Bible teaches that “whoever calls on the name of the Lord will be saved” and “the one who seeks, and keeps on seeking, will find”. So if you or someone else calls, I believe he will answer (though we may not always recognise it).

(2) We don’t know how anyone’s lives will end up, so there may be some who have not yet been given faith, but will be some day.

(3) We don’t know why God gives faith to some and not to others. I can only think that God will be more fair, not less fair, than I would be. My guess is that God gives faith to believe to anyone who is honestly seeking in the right way.

(4) But in saying these things, I am not therefore saying anything about the integrity of any particular person, you, Russell, or anyone else. I don’t pretend to speak for God, and I accept the genuineness of many atheists I meet on the web. I don’t know how any of you will end up, exactly why you disbelieve, how God will judge you, or anything, and I am not in any position to make a judgment. I can only try to answer your question.

Thanks.

LikeLike

Hi UnkleE

In essence I see that there are three basic possibilities:

1) ‘God’ will see me as someone genuinely seeking truth and show me the truth;

2) ‘God’ will in essence say I am not really seeking truth, that is I am in some way insincere and blind me to the truth; or

3) There may not actually be a ‘God’ there to find.

Being someone who was a believer, in my view and the view of every person who knew me, I could argue that Hebrews 6:4-6 says if someone like me falls away there is no coming back. So even if the Bible is true my position is hopeless. Having said that I am yet to come across a single person who really believes that particular text applies in reality.

LikeLike

Hi Peter, I missed this for a day or two, sorry. I see some other possibilities ….

1a. God will see that you are genuinely seeking the truth and try to show you, but you may have the wrong assumptions or seeking in the wrong way, and so miss it.

4. God sees you are not really seeking the truth but loves you anyway and tries again to turn your head in a different direction.

5. You will come to see that you knew the truth back then and have temporarily misunderstood, and you get back to it eventually.

I suppose they are subsets of your options, but I think they are important.

I think many christians and non-christians alike misunderstand the Bible because they apply it like a 21st century science text. I’ve heard some OT scholars say to the Jews, the Bible is less a statement of doctrine and truth and more like a discussion with different viewpoints. (e.g Proverbs 26:4-5 give to opposite views one after the other!) I think there’s at least some truth in that. Hebrews 6 expresses some truths but there are other ways of looking at it too. In some ways which truth applies to us depends on our response.

I accept you were a genuine believer as much as any human being can make that judgment. I sincerely hope you are able to find good reasons to believe again one day.

LikeLike

I don’t see Proverbs 26:4-5 as a problem, rather I see it as saying no matter what you do you can’t win with a fool. Regardless of whether you engage with them or decide not to, they will consider they have won the argument. I can testify to the efficacy of that from my dealings on some other blogs.

LikeLike

I got a rueful chuckle out of that one! I have been accused of that, as well as thinking that of others, sometimes at the same time! 😦

LikeLike

Curiously, WordPress has stripped out my paragraph numbers and the gaps between paragraphs. Sorry it is now slightly less readable.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know it does that to me sometimes. No worries at all. It was perfectly clear though I’m fairly confident that I still managed to misunderstand you in numerous places. Haha. 🙂

LikeLike

Hi Russell

I found your post extremely interesting. I too was once a Christian but am now a non-believer. The part about the want to have faith because it is such a hopeful and euphoric feeling certainly hit home. Eventually, I found faith such a struggle when I have such a rational mindset that it felt like I was fighting against every inch of my own personality in order to maintain it.

It is so refreshing to hear somebody discuss religion so calmly, thoroughly and without judgement.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have weeded the word ‘faith’ from my vernacular. It carries too much baggage, as you have so eloquently shown. I found that where I was using ‘faith’, ‘confidence’ would usually do the job better. When I believe in something without concrete reason, my thoughts are imbued with hope, not stubborn certainty. In the end, I am not willing to spend my life betting on shaky reasoning.

LikeLike

Hi Russell, I am quite fine with lots of quotes and responses. The only difficulty is that it can grow exponentially, so I will confine myself to four topics (if I can!).

“why I think there are better hypotheses that are simpler, with fewer new dependencies, that also fit the data, make accurate predictions and provide control.”

I think this misses the point of the argument from strong personal experience of God. You are still arguing evidence and rationality, etc. But this argument says that beyond all evidence and rationality, it is possible for God (who after all can do anything that is consistent with his character) can give a person an experience and a certainty about that experience that is truly and actually so certain that it blows all that you can say away. You can say quite rightly that the methodology is poor and the person could be fooled, and you’d likely be right according to logic, but if God is really there and has really directly interacted with that person, then your logic is of no value. I’ll give two examples, neither proving everything I want to say, but each adding something.

First, there is a story (not sure if true) of when Mike Tyson was at the peak of his boxing career, and he was being interviewed about his next fight. The reporter says “Your next opponent says he has a plan to beat you, what do you say about that?” Mike is reported to have said “They all have a plan – and then I hit them!” There is a simple ratio equation – God:your evidence > Tyson: plan.

Second, a detective investigates a case, methodically putting evidence together, finally showing that of all the possible suspects, you are the only one who is without an alibi, had a motive, had the means to do it, etc, and charges you. Yet you know that you didn’t do it. You might get convicted and go to gaol (later DNA studies show many people are wrongly convicted) but still you know you didn’t do it.

Now in the end, there is nothing anyone can say to the person who believes they have directly experienced God in a very deep way. You can say the evidence isn’t strong enough, they will say it is. I say they will legitimately believe, and it is only the rest of us who have to decide whether the evidence is strong enough.

Let me repeat, I have never had such an experience, and I am not using it as an argument for my belief (although I think the cumulative sum of such experiences can be a reason for outsiders like me to believe, because each event adds to the probability that God exists). But I still think it is quite wrong to suggest that the experiencer is wrong to believe on that basis.

“No, science does not help us know what God is. Science tells us what God is unlikely to be. …. I think the very idea of “knowing God” through any means is wrong-headed. God is by definition supernatural. Outside of nature. Because of that, our thoughts about God are indistinguishable from our imaginations about a made-up God, except where our ideas of him require interaction with the physical world – in which case, science is the only way we can “know” anything about God”

I disagree here. We only know anything outside of ourselves via our senses. How do we know our senses give us reliable information? Because what we learn from them is verified by others, is consistent and allows us to make decisions about our actions that give predictable results. We could probably think of other criteria.

Using the same sort of criteria, we can scientifically test some personal experiences (visions, healings, mystical experiences, etc) and when we do it is arguable that there is consistency there too, and they lead to predictable and good effects, etc. Again, this isn’t certain, but it increases probability.

Also the major philosophical arguments for the existence of God rest on current science. So I think some level of science is useful in assessing whether God exists, it just isn’t the only thing we should use.

“I understand and respect this position. I used to hold it myself. I’ll just say that I can’t find any way back to that place, despite how much I long for it, because no set of reasons for trusting the Bible that I can come up with are not better explained by the reasons to distrust it.”

I think this is a key issue. I don’t think my comment mentioned the Bible as an authority, and I don’t think belief in God or Jesus depends on belief in the Bible. Rather, a growing number of christians say that belief in the Bible follows belief in Jesus. It works like this.

I look at the philosophy and science, at my rather modest personal experience of God, and documented cases of others’ apparent experiences of God, and I form the view that it looks quite possible that God is there. So I come to the life of Jesus, not looking at the Old Testament at all, and not looking at the New Testament as “inspired” or “authoritative” or “trustworthy” at all, but merely as a historical document (or really a group of documents). I look at what the secular historians conclude about it, and take what is the consensus as a reasonable starting point.

On that basis I ask myself what is the right conclusion to come to about Jesus? And since I have already concluded that it looks quite possible, even quite likely, that God exists, I make my judgment on that basis. And on that basis, I am willing to accept he really does appear to have healed people (the historians agree that was what he was known for), he really did act like God’s unique envoy on earth, and he really was resurrected (the historians generally agree his tomb was empty and his followers really did see visions of him after he died).

So I decide I believe in him. Then, and only then, can I consider whether the Bible is something more than the historical documents of the historians.

So I don’t think lack of trust in the Bible is a reason to disbelieve in Jesus – it requires a lack of trust in secular historians!

“If you took out the faith part, and just trusted Jesus based on the evidence alone, and trusted your wife was right for you based on the evidence alone, would it change anything? If not, then what is faith doing in your belief equation? Why use the word at all?”

Again, this is a key question, especially to the topic of your post. It is a difficult one to answer, because I have to try to understand my own motives, including subconscious ones. I’ll do my best, but I may change my mind later. I think there are several levels of faith.

First, we only have one life, and we live and die by our choices. I believe the evidence for Jesus and God is way stronger than the evidence against, but is certainly short of certainty. I could decide to wait a little longer, get some more evidence, but I am a person who would prefer to make a choice and get on with it. (e.g. I married at 21. I used to be an environmental manager, and the best way to manage the environment is not to wait until we know all we need to know – everything would be stuffed by then – but to make the best choices we can, and then review them and adjust course – it’s called adaptive management). I have done the same with christian faith, which I am constantly reviewing and adjusting. Some people would call the gap between probable evidence and committed belief “faith”. I don’t think I use it much that way, but I see their point.

Second, Einstein and Hawking have each said something to the effect that we have the laws of nature that control the evolution of the universe from the initial big bang, but we don’t know “what breathes fire into the equations” and actually makes the universe happen. In my life when I was 16, I spent a period of about a year believing that christianity was true, but not committed to following Jesus. I finally committed, and I think that was a step of faith. Faith “breathed fire” into the evidence and led me to act and commit.

Third, and this is the most important one I think, CS Lewis points out that life is not just intellectual, but also emotional and spiritual. People can be discouraged or disillusioned enough to give up and disbelieve. He argues that when that happens, we should review the evidence – are our reasons to believe still true? If so, then we know our discouragement is emotional. That is when we exercise faith to keep going, when we feel it is all false but know it is still true. I have followed his advice literally hundreds of times in my 50+ years as a christian. That is where faith comes in.

Fourth, once I am a christian, I am faced with issues relating to prayer, guidance, understanding the Bible, etc. As a christian I make many decisions “in faith” that God is leading me. Here faith is trusting that the God I intellectually believe is there will act according the character I believe he has.

Sorry, my response is long too. I am only new to this blog, and hopefully as we get to know each other more, I can answer more briefly. Thanks for the opportunity.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi unkleE,

Okay, you’re right. This is getting long. Haha. I’m going to be more direct this time to save words and time, but since you can’t hear me talking or see my body language, please know my tone is in no way harsh. I know some of this will sound critical when reading but it isn’t meant that way or typed out with a single scowl. More smiles and inquisitive looks than anything. 🙂 Here goes…

You quoted me saying…

and you said

We seem to agree here, with slight clarifications. To be clear, my arguments here have never been about whether or not a God could do such a thing. I’m questioning whether forming extremely strong beliefs based on what we think is a poor line of reasoning is the best way to reach conclusions that are True. I’m not arguing that a God could not exist that could convince people of things on weak evidence. In fact, I agreed with that a few times. Such a God might exist. What I’m saying is that believing things on weak evidence, with high confidence, is what many people call “faith.” Some people believe with certainty that such convictions are from a God they believe in. This causes great problems. Other’s believe that, since such convictions are subject too all the same fallacies the as default poor human reasoning that hasn’t been filtered through a methodology to remove human biases and logical fallacies, it’s not a good mechanism to use and thus they don’t like the notion faith.

I liked your stories but I wasn’t really clear about whether you thought they conflict with the notion that being certain of things we “think + hope” are true should not make us certain that they are true. That wasn’t worded well, sorry. My time is short and there’s a lot to respond to. 🙂

This is the problem I referenced. It seems humans have been experience God and believing things with certainty based on faith for over a hundred thousand years. The vast majority of human life has claimed some kind of knowledge about what their God is like and wants and changed their beliefs and behavior due to this strong impressions. Option 1 is that there is a God or Gods out there playing with human minds and granting them certainty in things that oppose the things they grant to other minds with certainty. If this option is correct, a person who stands on faith can’t judge another person who stands on faith, despite their beliefs, because their subjective experience tells them that whatever they believe they can know is from God because of their personal evidence. Gods in this instance sound more like the warring Gods who fight among themselves and play with humanity. Option 1, may be true. It is certainly possible. Maybe a version of the Christian ideology is correct and demonic forces are deceiving part of humanity and all of humanity some of the time. But that line of reasoning is recent in the timeline of conscious man, and faith has been along far before the concept of Yahweh and Satan. In addition, option 1 is only an unlikely possibility while option 2 is clearly demonstrable with overwhelming evidence. They may both be true, but only one is obviously true. Start with the option 2 which we can know to be true. If it explains all the data, then what need to posit option 1 on top of it?

Option 2 is that human reasoning was bread more for survival than truth. We suffer from hidden logical fallacies and biases. Science is the process of removing those blind spots so we can reason better. If we don’t know what the blind spots are, we can’t possibly say whether or not they’re effecting our conclusions and our certainties, or to what degree they are affecting them. In retrospect, that is probably one of the main themes of my views on faith. Faith increases certainty without accounting for the blind spots. The blind spots are affecting many conclusions for all of us, only some people choose to actively learn about them and reign in their certainty accordingly while others remain unaware and claim they know X or Y because of their personal evidence. If we understand innumeracy (our innate misunderstanding of large numbers), confirmation bias, pattern matching, the fallacy of affirming the consequent, motivated reasoning, and on and on, and if we then apply each of them examine our personal experiences to see which were possibly modified by them and to what degree, taking nothing as certain but rather as probabilistic, then what beliefs remain will have a confidence level and a margin of error that we can stand on with confidence.

Otherwise our faith feels solid but it’s a house of cards and we’re often unknowingly pitted against science. I personally know very view conservative evangelicals who trust science at all. Anti-intellectualism and ant-science education often has it’s roots here, and lack of science education is preventing us from preventing more suffering and death. We probably agree that we need more scientifically literate believers of all faiths who can promote their faith with solid rational that everyone can accept and condemn the ends of the bell-curve in every faith who hold to extreme views that have negative impacts on humanity.

In addition, if we don’t filter against the fallacious and biased thinking that most of us are largely unaware of, it seems like we’re just riding our flawed human reasoning and assuming, incorrectly, that we know truths about the supernatural. It may be that one or more of our beliefs about the supernatural is correct (I’m avoiding the term “know” because we can technically have no “knowledge” if any belief about a supernatural is correct or if anything outside of nature exists), but if subjective evidence (feelings) rule, by what objective standard is our knowledge any more demonstrably correct than anyone else’s, perhaps those who wish us harm? I’m not trying to get into a morality debate here and now (goodness this is long already, haha), but I want to point out some of the many pitfalls to a system of coming to beliefs that rely on how we feel about evidence more than the objective defensibility of that evidence. We will always have a right to believe what we wish, because ultimately all beliefs are subjective just as the experiences that provide them are. But some systems are better than others at managing extreme views.

Option 2 is true. We have imperfect reasoning due to evolution. It explains all human religions and all faith. There could be a God or many Gods adding to the confusion and granting different clarity about different things to different people, but that hypothesis is unnecessary and adds complexity, challenging Occam’s Razor.

All evidence, whether objective or subjective, is “experienced” and thus is subject to the flaws in our reasoning. As such, all evidence needs to be examined against the known holes in human reasoning before a decision is made. If we 1) have a good understanding of the holes in human reasoning and how to close them, 2) examine our experience of the evidence against these holes, 3) put a probability and margin of error around our conclusion (can be subconscious), 4) still believe the evidence is strong enough for positive belief and can explain why such that unbiased listeners who understand this process will agree that it is sound, then 4) we are arriving at our belief based on the evidence alone and faith isn’t part of the equation. Otherwise, we’re at the whim of flawed human reasoning and our chances of finding truth are diminished while our chances of finding certainty are increased (a bad recipe).

Technically, I agree because all beliefs are legitimate to the person believing them. Legitimacy depends on who or what is imposing the rules, however, and the believer is not the only authority involved in most beliefs. Beliefs do not live in a vacuum and they often affect other people. For this reason, there are social contracts and governmental laws that legitimize behaviors based upon beliefs. The legitimacy of a belief may also be challenged by reasoning forums like a church, social club, cultural group, philosophical body like science, etc. A persons beliefs will always be legitimate to them, sometimes to one or more social groups they’re operating within, and very rarely within all social groups. What I’m saying is that personal beliefs may not be legitimate according to the best methods we have of reasoning to truth, and that is the point of this post. To do that, a belief must be filtered through the fallacies and biases discovered by logic or science.

Does each anecdotal experience add to the probability that God exists? Not for me. It would have to be a case-by-case question, but I haven’t heard any yet that sound compelling upon investigation. Most tales grow with the retelling. I don’t suggest an experiencer is wrong to believe anything. I’m not trying to control beliefs. I’m trying to establish that there is an arena of methodologies that have been thoroughly tested and proven to be more likely to come to true beliefs than false ones. If a believer wants to have an appropriate level of confidence in their belief, they can come and learn those methodologies and critically apply them to their beliefs, especially their closely held ones. If they do this, they’re level of commitment to their belief is appropriate to the other people who work in that arena. It can be passed along as a legitimate experience that led to a legitimate belief. If not, it will be rejected by the larger communities that deal with reason and logic and they may lose their membership for a time. 🙂 This happens between all disparate communities of thought, not just between faith and science. If we express pro-political party A beliefs to political party B, they may find our beliefs or reasons illegitimate. Is there a set of belief systems that has been refined over many years to be as bias and fallacy free as possible that can act as an arbiter to decide legitimacy between all these belief systems? The closest we have is science. That’s what it’s been bread for.

I agree with you. 🙂 I disagree with that part of my quote as well because it’s not the full thing. I ended it with…

What I was trying to say was that if God starts interacting with the laws of nature, we can test and know something is messing with the laws here. If it’s happening in a way to confirm a Biblical predication (e.g. people of faith X prayers are answered regularly but people of faith Y’s aren’t) then we can have some confidence, via science, that God X may be the most likely hypothesis. Science will entertain God hypothesis and adapt to them, it just hasn’t even found one God hypothesis more likely and doesn’t currently assume a God as a cause for anything in its methodology.

On the other hand, if claim X and Y are made about God Z, and the claims are mutually exclusive, we can use science to determine that it’s not likely that God Z exists with both of those attributes in the same way at the same time. He may in some supernatural realm, but the attributes have to mean something different in this realm or we can’t have high confidence in them because they break logic which is a subset of the inclusive version of science. Also, if it’s claimed that God interacted with the world in detectable way X, and measurements are made but way X did not occur, science can say that claim was not validated so the hypothesis that supported that claim is now less likely. These are just a few examples.

I’d go further by saying we the steps between our senses and conscious understanding of them is also subject to failures.

We know they do not give us reliable information. If you think they do, please listen to that book. 🙂

Okay, I’ll rephrase. Our sense are not completely reliable. We can have more confidence in them experience things from them that are verified by others, but even that does not give us completely trust in out senses as groups of people can easily be deceived.

Except when you examine these closely they don’t pan out. They overwhelmingly more examples of flawed human reasoning. They fit in with UFO abduction stories and big foot sightings in terms of actually successful verification rate. This does not increase probability. If anything, it decreases it. The initial positive reports are almost always due to poor control because the experiment was carried out by professional scientists and no miracle claim I know of has made it through peer-review. Not all scientists understand the clumpiness of randomness and the probability that some set of experiments will disprove the null hypothesis simply because P-values are imperfect. Perhaps they’ll be changed as the philosophy of science evolves. A small P value – low probability of the data they measured – might mean the null hypothesis is wrong, or it might mean they just saw some unusual data. They can’t “know” which with one trial, which is why multiple experiments all of the world under different conditions with many seasoned scientists trying to disprove the hypothesis (rather than prove it) and a process of peer-review where more scientists pick it apart for wholes in reasoning, flaws in data collection, etc. may signal possible weakness in the conclusion arrived at by the experiment results (the scope of the conclusion is also tested). None of that is relevant, though, since no claimed subjective experience or miracle has even made it through one scientific test that didn’t come back with a different and more likely explanation than a supernatural event. Of course, science would lean toward the natural, so it’s always possible a real miracle is a work. But how would one know that?

Here’s what I mean. Science identifies consistencies in nature which are constantly tested in an effort to disprove them. It’s always looking for the unique and unusual. Something that will defy a known consistency (e.g. a “law” or “theory” if it provides explanation) is extremely scientifically interested and could win a Nobel Prize (many scientists’ dream). A miracle is exactly that thing they’re looking for. Want to overturn an existing principle in science and learn new questions to ask to unlock new mysteries of the universe? Find an anomaly. Find a miracle! If you can do that and demonstrate it, the world shakes. So, with that motivation in mind, it’s not so clear that science is turning a blind-eye to potential anomalies like miracles. But none have been found. Just nature at work following the laws we know within the size and time of things relevant to human events. The standard model of particle physics explains everything relevant to us so far. It also explains supernatural feelings. We go into a lab and a scientist can trigger a supernatural experience by sending magnetic pulses to certain parts of our brains. If the experience of supernatural phenomena can demonstrably, objectively be both measured and triggered within the framework of the consistent things we understand about nature, how can we be certain that the experience actually comes from something outside of nature? We can’t (the fallacy of affirming the consequent). That’s something I struggle with. The only workaround to get there is usually faith. But again, that’s a modifier that goes beyond the evidence. We can’t know, and I’d rather be honest with myself and assign a confidence level and margin of error around any claimed miracle and refine it as I collect more evidence. Nothing has been conclusively miraculous yet. You very likely know of some claims that I don’t and you obvious reason differently which explains our different conclusions.

It has to be that way, unfortunately. With that said, there are some things that we’ve demonstrated that are extremely unlikely to ever change and those things say a lot about old God-claims that defy observation unless this is the devil’s workshop. If God wants to interact with the world and be detectable in the future, science will be very happy to try to do the detecting. Until then, current science is enough for the conclusion that a God, if he is anywhere, is not obviously changing the laws of nature in any noticeable way on a consistent basis that would make his presence obvious. If he interacts at all, he does so only in the parts of human experience and reasoning with the flaws and holes in it so that we can’t know if it’s a God causing an anomaly to increase our belief or if it’s our evolution-built imaginations (looking at other faiths, we have high confidence that the latter is at work) following natural laws we already understand.

I completely agree. But when we find things that overlap with sciences domain we should employ it. Science isn’t a thing but a process. A way of thinking to determine whether something is more likely reflective of the reality that IS. If, for example, a God-claim was made that said if you do “this” he will do “that” in the world, we should test this and that with science. Such a test could never demonstrate the cause of “that” must have been a supernatural being that was described (that’s out of science’s domain and constitutes the fallacy of affirming the consequence), rather than some other force, but it can be evidence to support that conclusion. In that way, science can support a supernatural agent operating in the world, but it is much more useful in what it says about God-claims that probably don’t exist in our reality. Other than science, which is requires repeatable experiments and constant behaviors, we can use one-time events as evidence for God, but we should subject them to the filter containing the possible other explanations before we decide how much weight to give such experiences.

You quoted me saying…

Then you said..

I think some people may come to a belief in Jesus without believing the Bible is true, but the percentage is likely small. Either way, someone is usually telling them about it, so they believe based on culture, word-of-mouth, family/friend-influence, etc. It matters not where the information is coming from. What I’m saying is that regardless of how I came to my belief (which was originally from family influence, church influence, trust in the Bible and many other factors that fueled personal experiences of Jesus in my heart), I would doubt them if I began to doubt the thing they stood upon. The Bible is the foundation of the faith. If trust in it crumbles, faith usually weakens.

I do the same and have the same conclusion. An infinite number of deities are possible. Some are more likely than others. Our existence is a mystery to me, for which I hold many possibilities in mind but the only somewhat strong conclusion I have is that I’m wrong to some extent in all my theories. It’s certainly possible that something we might consider a God is in there somewhere. If I were a horse, no doubt I’d think he had many horse attributes. As as software architect I imagine the being running a simulation with us as a tiny fraction of the actors. That theory fits all the data, but I’m very aware that the odds that it’s correct are approximately 1/infinity. I’m a possibilian.

Good. I do this too and don’t find a strong consensus. I also tend to trust the more objective ones, which are hard to identify. Many secular Biblical historians are not objective, but on average, those who are sold out for the faith are even less so.

Historians are reading stories put down by men who were at least as subject to the problems in human reasoning that we are today (very likely more so), and didn’t have a solution for them. The conclusion that the tomb was empty is gathered from the stories themselves and doesn’t account for the possibility of it being stolen the first night. I’m currently around 60/40 for the idea that Jesus existed and I have two more books to read (one for and one opposing) before updating that confidence level. That makes the empty tomb a moot question at this stage. I’m 50/50 on the existence of something like a God. I disagree with Paul that men are without excuse. Maybe there was an excuse in his time when so much of everyday nature wasn’t understood and assumed to be the direct active influence of God, including a life spirit, demons, and the belief that a force was required to keep the heavens in motion – which we now know to be the passive force of gravity and the conservation of momentum in the frictionless void of space rather than God or the angels pushing things around. God could still be actively making gravity look consistent and passive and preserving momentums of objects that don’t have other influences acting against them. However, as Laplace said to Napoleon when asked why there was no mention of the solar system’s Creator in his Celestial Mechanics, “I had no need of that hypothesis.”

It sounds like your saying you didn’t put much weight whether or not the Bible is trustworthy but then you did put weight in what historians had to say about a story in the Bible and then decided to believe it. From that it seems that you did put trust in the Bible, just more indirectly. I’ve always struggled with this verse as much as any other. I’m curious about how you approach it. Do you think Matthew 27:51-52 is an accurate description of events. If it is accurate, why do you think we have no record of it from any of the historians writing in Jerusalem in or about the time of the events and why do you think it wasn’t in any of the other gospel narratives of the crucifixion? Everything is basically the same between the stories except the author of Matthew or some later editor just throws this in. If it isn’t accurate, how much trust should we give the rest of Matthew’s work?

Back to you…

Okay. I get this. But it does sound circular in any other context, right? You’re trusting that the story that the book relates is reliable without asserting that the book that relates it is reliable, right? If we believe an ancient document not because we think it’s true, but because some of the historians think this part is true while others don’t, and then we decide to trust in the hero of the story, and based on that trust we decide to also trust what the document says in the other parts… it’s a circle. Part of the Bible–>Historians–>Us–>More of the Bible. Either way, it still stands or falls on your trust of the Bible, and I lack that. You know how we probably both think that it’s more likely that flawed human reasoning led to the stories in any other religions belief system (which are only a tiny fraction of those we’ve believed of the hundred + millennia) than that actual supernatural events did. In exactly the same way that we don’t fully trust that the supernatural events that support pick-your-religion-other-than-your-own, I don’t trust that the Bible is an accurate account of those events. Since it is more than likely not accurate, I think it’s more than likely inaccurate about the supernatural claims as well.

All of the explanations I hear about the Bible not being a requirement for Christian belief seem to still ultimately come back to trust in the Bible for belief.